WILDERNESS: WHAT and WHY

WILDERNESS: WHAT and WHY

By Howie Wolke

A few years ago, I led a group through the wilds of northern Alaska’s Brooks Range during the early autumn caribou migration. I think that if I had fourteen lifetimes I’d never again experience anything quite so primeval, so simple and rudimentary, and so utterly and uncompromisingly wild. If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, this beheld my eye above all else. Maybe that trek—in one of the ultimate terrestrial wildernesses remaining on Earth—is my personal yardstick, my personal quintessence of what constitutes real wilderness among a lifetime of wilderness experience. The tundra was a rainbow of autumn pelage. Fresh snow engulfed the peaks and periodically the valleys, too. Animals were everywhere, thousands of them, moving across valleys, through passes, over divides, atop ridges. Wolves chased caribou. A grizzly on a carcass temporarily blocked our route through a narrow pass. It was a week I’ll never forget, a week of an ancient world that elsewhere is rapidly receding into the frightening nature-deficit technophilia of the twenty-first century.

Some claim that wilderness is defined by our perception, which is shaped by our circumstance and experience. For example, one who has never been to the Brooks Range but instead has spent most of her life confined to big cities with little exposure to wild nature might consider a farm woodlot to be “wilderness.” Or a small state park laced with dirt roads. Or, for that matter, a cornfield, though this seems to stretch this theory of wilderness relativity to the point of obvious absurdity. According to this line of thought, wilderness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.

Yet those who believe that perception defines wilderness are dead wrong. In our culture, wilderness is a very distinct and definable entity, and it can be viewed on two complementary levels. First, from a legal standpoint the

Wilderness Act of 1964 defines wilderness quite clearly. A designated wilderness area is “undeveloped” and “primeval,” a wild chunk of public land without civilized trappings that is administered to remain wild.

The

Wilderness Act defines wilderness as “untrammeled,” which means “unconfined” or “unrestricted.” It further defines wilderness as “an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent human improvements or habitation.” The law also generally prohibits road building and resource extraction such as logging and mining. Plus, it sets a general guideline of 5,000 acres as a minimum size for a wilderness. Furthermore, it banishes to non-wilderness lands all mechanized conveniences, from mountain bikes and game carts to noisy fumebelching all-terrain vehicles and snow machines.

Written primarily by the late Howard Zahniser, the Wilderness Act creates a

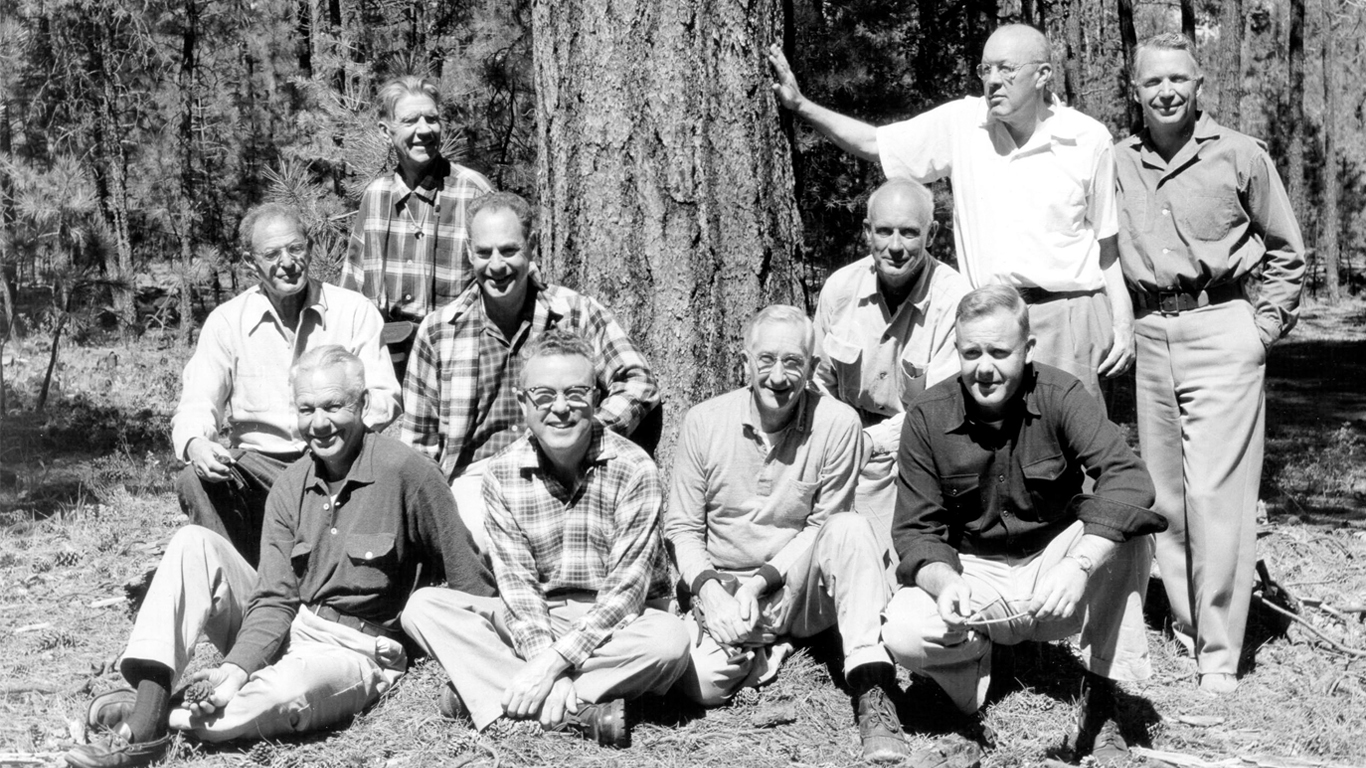

National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS) on federally administered public lands. All four federal land management agencies administer wilderness: the U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bureau of Land Management. Under the Wilderness Act, the NWPS is to be managed uniformly as a system. And an act of Congress followed by a Presidential signature is required to designate a new wilderness area.

In addition to wilderness as a legal entity, we also have a closely related cultural view, steeped in mystery and romance and influenced by our history, which yes, includes the hostile view of wilderness that was particularly prevalent during the early days of settlement. Today, our cultural view of wilderness is generally positive. This view is greatly influenced by the

Wilderness Act, which means when people speak of wilderness in lieu of legal definitions, they speak of country that’s big, wild, and undeveloped, where nature rules. And that certainly isn’t a woodlot or cornfield. In summary, then, wilderness is wild nature with all her magic and unpredictability. It lacks roads, motors, pavement and structures, but comes loaded with unknown wonders and challenges that at least some humans increasingly crave in today’s increasingly controlled and confined world. Untrammeled wilderness by definition comes with fire and insects, predator and prey, and the dynamic unpredictability of wild nature, existing in its own way in its own right, with utter disregard for human preference, convenience, and comfort. And perception. As the word’s etymological roots connote, wilderness is “self-willed land,” and the “home of wild beasts.” It is also the ancestral home of all that we know in this world, and it spawned civilization, although I’m not convinced this is a good thing. So wilderness isn’t just any old unpaved undeveloped landscape. It isn’t merely a blank space on the map. For within that blank space might be all sorts of human malfeasance that have long since destroyed the essence of real wilderness: pipelines, power-lines, water diversions, overgrazed wastelands, and off-road vehicle scars, for example. No, wilderness isn’t merely a place that lacks development. It is unspoiled and primeval, a sacred place in its own right. Wilderness designation is a statement to all who would otherwise keep the industrial juggernaut rolling: Hands off! This place is special! Designated wilderness is supposed to be different “in contrast with those areas where man and his works dominate the landscape.” (Wilderness Act, section 2c)

Nor is wilderness simply a political strategy to thwart bulldozers from invading wildlands. That’s one valid use of our wilderness law, yes, but when we view wilderness only—or even primarily—as a deterrent to industry and motors, we fail to consider all of the important things that differentiate real wilderness from less extraordinary places. Some of those things include tangible physical attributes such as native animals and vegetation, pure water, and minimal noise pollution. But in many ways, the intangible values of wilderness are equally important in differentiating wilderness from other landscapes. Wonder and challenge are but two of them. For many of us, the simple knowledge that some landscapes are beyond our control provides a respite of sanity. Solitude and a feeling of connectedness with other life forms are also best attained in wilderness. Wilderness also provides us with some defense against the collective disease of “landscape amnesia.” I began to use this term in the early 1990s while writing an educational tabloid on wilderness and roadless areas. It had begun to occur to me that, as we continue to tame nature, each ensuing generation becomes less aware of what constitutes a healthy landscape because so many components of the landscape gradually disappear. Like the proverbial frog in the pot of water slowly brought to a boil, society simply fails to notice until it’s too late, if it notices at all. For example, few alive today remember when extensive cottonwood floodplain forests were healthy and common throughout the West. So today’s generations view our currently depleted floodplains as “normal.” Thus there’s no impetus to restore the ecosystem. This principle applies to wilderness. Wilderness keeps at least some areas intact, wild and natural, for people to see. We don’t forget what we can still see with our own eyes. Moreover, when we keep wilderness wild, there’s little danger that as a society we’ll succumb to wilderness amnesia, and forget what real wilderness is. Perhaps the most important thing that sets wilderness apart is that real wilderness is dynamic, always in flux, never the same from one year or decade or century to the next, never stagnant, and entirely unconstrained despite unrelenting human efforts to control nearly everything. Natural processes such as wildfire, flood, predation, and native insects are (or should be) allowed to shape the wilderness landscape as they have throughout the eons. Remember, wilderness areas are wild and untrammeled, “in contrast” with areas dominated by humankind. That domination includes our interference with the natural forces and processes that shape a true wilderness landscape. It has been said that wilderness cannot be created; it can only be protected where it still persists. There is some truth here, but there’s a big gray area too. Even though most new wilderness units are carved out of relatively unspoiled roadless areas, Congress is free to designate any area of federal land as wilderness, even lands that have been impacted by past human actions, such as logging and road building or off-road vehicles. In fact, Congress has designated such lands as wilderness on numerous occasions. Once designated, agencies are legally required by the Wilderness Act to manage such lands as wilderness. Time and the elements usually do the rest. For example, most wildernesses in the eastern U.S. were once heavily logged and laced with roads and skid trails. Today, they have reattained a good measure of their former wildness.

Perhaps the most crucial but overlooked sections of the

Wilderness Act deal with caring for designated areas. The Wilderness Act quite clearly instructs managers to administer wilderness areas “unimpaired” and for “the preservation of their wilderness character.” This means that the law forbids degradation of wilderness areas. Therefore, you would assume that once an area is designated as wilderness, all is suddenly right with at least a small corner of this world. But you would be

wrong.

That’s because, despite the poetic and pragmatic brilliance of the Wilderness Act,

land managers routinely ignore the law and thus nearly all units of the

National Wilderness Preservation System fail to live up the promise of untrammeled wildness. To be fair, agency wilderness managers are often under tremendous pressure—often at the local level—to ignore abuse. Sometimes their budgets are simply inadequate to do the job. On the other hand, we citizens pay our public servants to implement the law. When they fail to properly maintain

wilderness character, they violate both the law and the public’s trust.

Throughout the NWPS

degradation is rampant. Weed infestations,

predator control by state wildlife managers (yes, in designated wilderness!), eroded multi-laned horse trails, trampled lakeshores, bulldozer-constructed water impoundments, the proliferation of structures and

motorized equipment use, over-grazing by livestock, and illegal motor-vehicle entry are just a few of the ongoing problems. Many of these

problems seem minor in their own right, but collectively they add up to systemic decline, a plethora of small but expanding insults that I call “creeping degradation,” although some of the examples seem to gallop, not creep. External influences such as climate change and chemical pollution add to the woes of the wilds as we head into the challenging and perhaps scary decades that lie in wait.

In addition to wilderness as both a cultural idea and a legal entity, there’s another wilderness dichotomy. That’s the dichotomy of designated versus “small w” wilderness. America’s public lands harbor perhaps a couple of hundred million acres of relatively undeveloped, mostly roadless wildlands that so far, lack long-term Congressional protection. These “roadless areas” constitute “small w” or “de-facto wilderness.” Here’s a stark reality of the early 21

st century: given the expanding human population and its quest to exploit resources from nearly every remaining nook and cranny on Earth, we are rapidly approaching the time when the only remaining significant natural habitats will be those we choose to protect—either as wilderness or as some other (lesser) category of land protection. Before very long, most other sizeable natural areas will disappear. In order to get as many roadless areas as possible added to the NWPS, some wilderness groups support

special provisions in new wilderness bills in order to placate wilderness opponents. Examples include provisions that strengthen

livestock grazing rights in wilderness, allow

off-road motor vehicles and helicopters, grandfather incompatible uses like

dams and other water projects, exempt commercial users from regulations, and much more. So we get legalized overgrazing, ranchers and wildlife managers on all-terrain vehicles, overzealous fire management and destructive new water projects, just to mention a few of the incompatible activities sometimes allowed in designated wilderness. This de-wilds both the Wilderness System and the wilderness idea. And when we allow the wilderness idea to decline, it is inevitable that society gradually accepts “wilderness” that is less wild than in the past. Again, it’s the disease of landscape or wilderness amnesia.

An equally egregious threat to wilderness is the recent tendency to create new wilderness areas with boundaries that are drawn to exclude all potential or perceived conflicts, also in order to pacify the opposition. So we get small fragmented “wilderness” areas, sometimes with edge-dominated amoeba-shaped boundaries that encompass little core habitat. Or legislated motor vehicle corridors that slice an otherwise large unbroken roadless area into small fragmented “wilderness” units. These trends alarm conservation biologists, who are concerned with biological diversity and full ecosystem protection.

Make no mistake, there’s a huge realm of unprotected public wildlands out there, and I’d give my right arm to get a big chunk of that largely roadless “small w” domain protected under the Wilderness Act. My arm yes, but not my soul. The soul of wilderness is wildness. When we sacrifice wildness by undermining the Wilderness Act, we lose both an irreplaceable resource and an irreplaceable part of ourselves. We lose soul. If we fail to demand and work for real wilderness, then we’ll never get it. That’s guaranteed. To some, particularly those who equate motors or resource extraction with freedom, wilderness designation seems restrictive. But in truth, wilderness is more about freedom than is any other landscape. I mean the freedom to roam, and yes, the freedom to blunder, for where else might we be so immediately beholden to the physical consequences of our decisions? Freedom, challenge, and adventure go together, and wilderness provides big doses of each. Should I try to cross here? Can I make my way around that bear? Is there really a severe storm approaching? When we enter wilderness, we leave all guarantees behind. We are beholden to the unknown. Things frequently don’t go as planned. Wilderness is rudimentary and fundamental in ways that we’ve mostly lost as a culture. This loss, by the way, weakens us. Wilderness strengthens us. Freedom. In wilderness we are free to hunt, fish, hike, crawl, slither, swim, horse-pack, canoe, raft, cross country ski, view wildlife, study nature, photograph, and contemplate whatever might arouse our interest. We are free to pursue our personal spiritual values, whatever they might be, with no pressure from the proclaimed authorities of organized church or state. And we are generally free to do any of these things for as long as we like. Wilderness is also the best environment for the under-utilized but vitally important activity of doing absolutely nothing—I mean nothing at all, except perhaps for watching clouds float past a wondrous wilderness landscape.

Wilderness provides numerous free services for humanity. It is an essential antidote for civilization’s growing excesses of pavement, pollution, technology, and pop culture. Wilderness provides clean water and flood control, and it acts as a clean air reservoir. It provides many tons of healthy meat, because our healthiest fisheries and game populations are associated with wilderness (Who says “you can’t eat scenery”?).

Another wilderness service is the reduced need for politically and socially contentious endangered species listings. When we protect habitat, most species thrive.

By providing nature a respite from human manipulation, wilderness cradles the evolutionary process. It helps to maintain connectivity between population centers of large wide-ranging animals—especially large carnivores. This protects genetic diversity and increases the resilience of wildlife populations that are so important to the ecosystem. We are beginning to understand that without large carnivores, most natural ecosystems falter in a cascade of biological loss and depletion.

Wilderness is also our primary baseline environment. In other words, it’s the metaphorical yardstick against which we measure the health of all human-altered landscapes. How on earth might we ever make intelligent decisions in forestry or agriculture, for example, if there’s no baseline with which to compare? Of course, wilderness only acts as a real baseline if we really keep it wild and untrammeled.

Wilderness is also about humility. It’s a statement that we don’t know it all and never will. In wilderness we are part of something much greater than our civilization and ourselves. It moves us beyond self, and that, I think, can lead only to good things. Perhaps above all, wilderness is a statement that non-human life forms and the landscapes that support them have intrinsic value, just because they exist, independent of their multiple benefits to the human species. Most emphatically, wilderness is not primarily about recreation, although that’s certainly one of its many values. Nor is it about the “me first” attitude of those who view nature as a metaphorical pie to be divvied up among user groups. It’s about selflessness, about setting our egos aside and doing what’s best for the land. It’s about wholeness, not fragments. After all, wilderness areas—despite their problems—are still our healthiest landscapes with our cleanest waters, and they tend to support our healthiest wildlife populations, particularly for many species that have become rare or extirpated in places that are less wild.

Having made a living primarily as a wilderness guide/outfitter for over three decades, I’ve had the good fortune to experience many wild places throughout western North America and occasionally far beyond. Were I to boil what I’ve learned down to one succinct statement, it’d probably be this: Wilderness is about restraint. As Howard Zahniser stated, wilderness managers must be “guardians, not gardeners.” When in doubt, leave it alone. For if we fail to restrain our manipulative impulses in wilderness, where on Earth might we ever find untrammeled lands?

Finally, when we fail to protect, maintain, and restore real wilderness, we miss the chance to pass along to our children and grandchildren—and to future generations of non-human life—the irreplaceable wonders of a world that is too quickly becoming merely a dim memory of a far better time. Luckily, we still have the opportunity to both designate and properly protect a considerable chunk of the once enormous American wilderness. Let’s not squander that opportunity. We need to protect as much as possible. And let’s keep wilderness truly wild, for that, by definition, is what wilderness is, and no substitute will suffice.

Howie Wolke co-owns Big Wild Adventures, a wilderness backpack and canoe guide service based in Montana’s Paradise Valley, near Yellowstone National Park. He is an author and longtime wilderness advocate, and is a past president and current board member of Wilderness Watch. This piece was published in "Wilderness: Reclaiming the Legacy." ©2011

by Kevin Proescholdt

by Kevin Proescholdt

An undercurrent of hostility toward wilderness boiled over in the U.S. House of Representatives when members passed H.R. 4089, the so-called

An undercurrent of hostility toward wilderness boiled over in the U.S. House of Representatives when members passed H.R. 4089, the so-called Jeff Smith is Wilderness Watch's membership and development director.

Jeff Smith is Wilderness Watch's membership and development director.