Wilderness Stewardship Concepts

Public Purposes of Wilderness | Minimum Requirement | Wilderness as a System

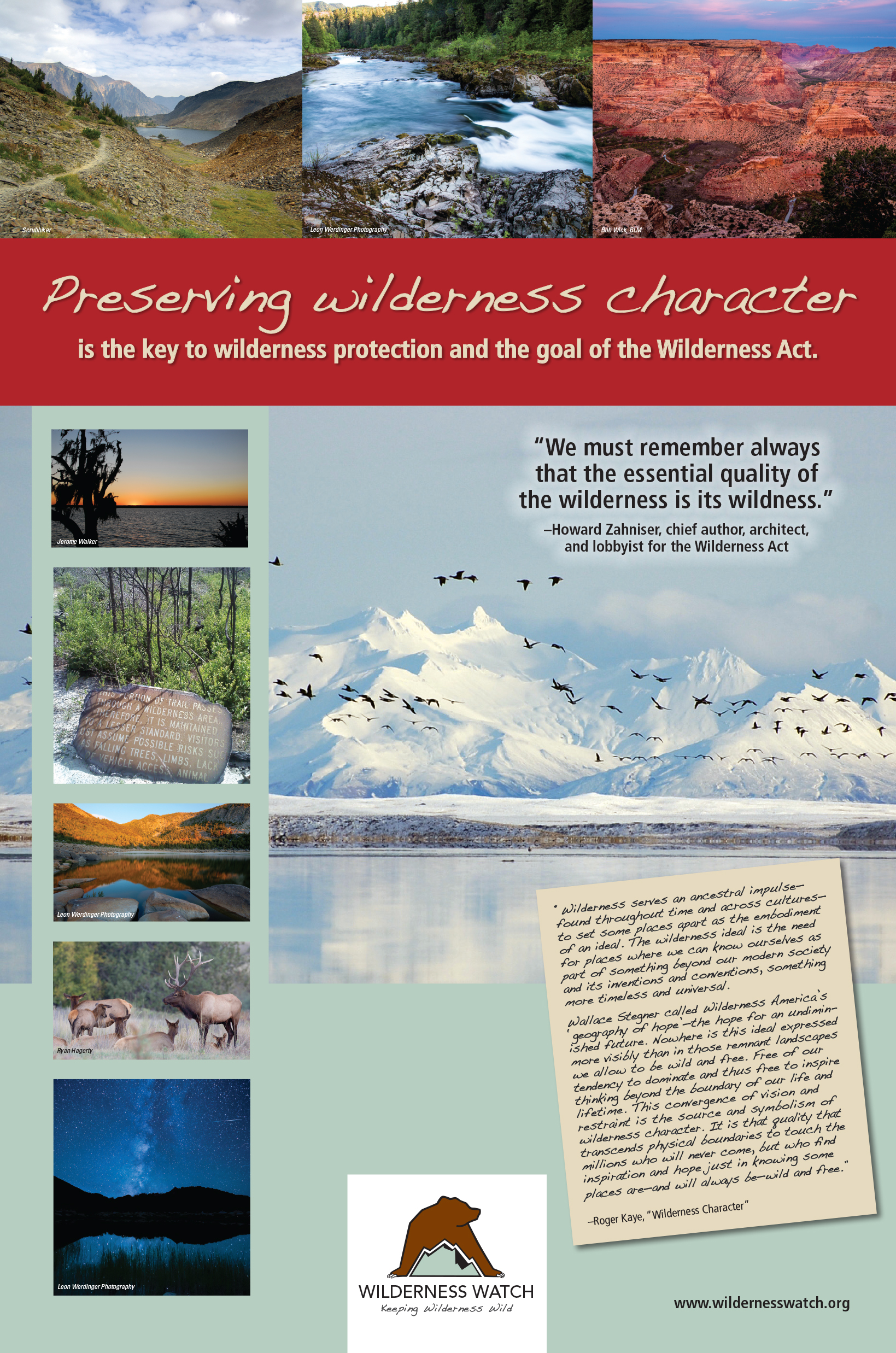

Wilderness Character

“The purpose of the Wilderness Act is to preserve the wilderness character of the areas to be included in the wilderness system, not to establish any particular use.” — Howard Zahniser, 1962

The overarching legal mandate of the Wilderness Act is to preserve the Wilderness character of each area in the NWPS. Preserving Wilderness character is the essential key to keeping alive the very meaning of wilderness in America. Despite its statutory importance, the concept of Wilderness character is not defined in the Wilderness Act, although the Act refers to it repeatedly. Section 4(b) of the Act explicitly mandates that managing agencies “shall be responsible for preserving the Wilderness character of the area and shall so administer such area for such other purposes for which it may have been established as also to preserve its wilderness character.”

The overarching legal mandate of the Wilderness Act is to preserve the Wilderness character of each area in the NWPS. Preserving Wilderness character is the essential key to keeping alive the very meaning of wilderness in America. Despite its statutory importance, the concept of Wilderness character is not defined in the Wilderness Act, although the Act refers to it repeatedly. Section 4(b) of the Act explicitly mandates that managing agencies “shall be responsible for preserving the Wilderness character of the area and shall so administer such area for such other purposes for which it may have been established as also to preserve its wilderness character.”Historical records clearly demonstrate that Wilderness Act visionaries believed that wilderness character consists of both tangible, physical components as well as intangible, psychological and spiritual components.

Some tangible components of Wilderness character include the presence of native wildlife at naturally occurring population levels; lack of human structures, roads, motor vehicles or mechanized equipment, lack of crowding or large groups; few or no human improvements for visitor convenience such as highly engineered and over-developed trails, developed campsites, signs, or bridges, and little or no sign of biophysical damage caused by visitor use, such as trampled or denuded ground, tree limbs cut for camp use, or habituated or displaced wildlife.

Some intangible components of Wilderness character include solitude; immediacy; opportunities for reflection; freedom; risk, adventure, and mystery; places where safety is a personal responsibility; untrammeled, wild and self-willed, where natural processes occur without intentional human interference; uncommodified, not for sale and commercial-free; opportunities for full self-reliance; opportunities for humans to experience our connection to the larger community of life; places that forever remain in contrast to modern civilization, its technologies, and contrivances.

Thinking in terms of Wilderness character is an extremely beneficial way of viewing all visitor use and management actions in wilderness. This concept refocuses our attention away from simply viewing wilderness as an amalgam of various biophysical resources and visitor experiences, to recognizing the relationship between these things and the overall Wilderness character of these special places. The concept enables us to view seemingly disparate management issues, proposals, and potential threats within the singular context of how well these will protect or diminish elements of Wilderness character.

Nondegradation

“Non-degradation of wilderness fundamentally should guide stewardship activities.” — Pinchot Panel for Conservation: Ensuring the Stewardship of the National Wilderness Preservation System, 2001

“Non-degradation of wilderness fundamentally should guide stewardship activities.” — Pinchot Panel for Conservation: Ensuring the Stewardship of the National Wilderness Preservation System, 2001The nondegradation principle applies to more than biophysical conditions in Wilderness; it is the essential key to protecting endangered experiences, experiences of a special quality and nature that are at risk of disappearing from our modern world.

The nondegradation principle is based on the mandate in Sec. 4(b) of the Wilderness Act to preserve Wilderness character in each area of the NWPS. It is Wilderness character that must not be allowed to degrade or diminish.

"Except as otherwise provided in this Act, each agency administering any area designated as wilderness shall be responsible for preserving the wilderness character of the area and shall so administer such area for such other purposes for which it may have been established as also to preserve its wilderness character." — The Wilderness Act, Sec. 4(b)

Congress can designate any federal land as wilderness, yet once designated, the stewardship of that area must not allow its wilderness character to diminish below the quality and amount that it possessed on the day it was designated. The concept of nondegradation applies to all aspects of Wilderness character, both its tangible and intangible components. Though all four managing agencies have adopted the nondegradation principle in their policies, few areas in the System currently meet that standard.

A policy of nondegradation can not be achieved without engaging the cause of degradation, as well as its effects. To this end, management intent is critical – does the intent of an action affirm our role as respectful guests and stewards of Wilderness? Or does it simply reinforce the “primacy” of our uses and benefits, our convenience and expediency?

When the intent of a management action is to achieve a goal that is unnecessary or unrelated to protecting an area as Wilderness, then wilderness character is often compromised in the process. Some examples are the manipulation of wildlife to favor game species; use of motorized equipment to construct and clear trails for visitor convenience; scientific research that involves modifying the Wilderness or using inappropriate equipment in Wilderness; and restoring or replacing old buildings (often with use of motorized equipment) rather than allowing them to naturally decay away.

Solitude

Section 2(c) of the Wilderness Act defines Wilderness, in part, as an area with “outstanding opportunities for solitude.” The Act clearly recognized the human need and benefits of seeking solitude from modern civilization, its pressures and technologies. Opportunities for solitude from civilization forms an intrinsic component of an area’s wilderness character. Good Wilderness stewardship requires protecting this important quality, and not allowing it to diminish over time. Carefully note that the Act does not require that individual visitors must want or appreciate wilderness solitude. The Act’s legal mandate to managers is that they are to preserve “outstanding opportunities” for visitors to experience this component of an area’s Wilderness character. This means managers cannot justify using motorized or mechanized equipment in Wilderness just because it is the ‘off-season’ when few visitors may be present. According to the law, Wilderness character must be preserved at all times, not just when visitors are present, and solitude is a key component of Wilderness character.

Wilderness solitude is diminished by actions and activities that are reminders of civilization, its conventions, and technologies. Solitude therefore can be diminished by the presence of crowding, large groups, intrusion of motorized vehicles and mechanized equipment, visible regulatory presence inside wilderness, habituation and displacement of wildlife, commercialized extreme sports, significant or dominant presence of other commercial activities, proliferation of recreation developments such as over-built bridges, wide trails, signs, restrooms, campsite benches, and hitching rails, and sense of immediate search & rescue availability.

Zahniser believed that experiencing solitude from civilization is very conducive to deriving the unique psychological and spiritual benefits of Wilderness:

“Deeper and broader than the recreational value of wilderness… is the importance that relates it (wilderness) to our essential being, indicating that the understandings which come in its surroundings are those of true reality… In the wilderness it is thus possible to sense most keenly our human membership in the whole community of life on the Earth. And in this possibility is perhaps one explanation for our modern deep-seated need for wilderness.”

Zahniser described an awareness of our membership in the larger community of life as the profound educational value of Wilderness. He believed that solitude from civilization is a key factor in enabling us to experience this benefit of Wilderness.

Purpose of the Wilderness Act

The Wilderness Act has one singular statutory purpose, and that is to secure the benefits of an enduring resource of Wilderness. This singular purpose is articulated in the opening paragraph of the Act as the Act’s Statement of Policy:

“…it is hereby declared to be the policy of the Congress to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness. For this purpose there is hereby established a National Wilderness Preservation System…”

As Howard Zahniser repeatedly testified to Congress during debate on the Wilderness bill, preserving Wilderness character is the essential key to securing an enduring resource of wilderness. The resource of wilderness and Wilderness character are inextricably intertwined. Without preservation of Wilderness character, the Wilderness resource would not exist.

It is also important to note that Congress explicitly refers to the wilderness resource as singular. It recognized that wilderness is more than just a collection of other natural resources such as wildlife, free-flowing streams, etc. These physical resources are important components of the wilderness resource, but the Wilderness Act’s emphasis on wilderness character demonstrates that Congress intended that wilderness be understood as more than just a mixture of biophysical resources. By congressional decree, wilderness is a complex and unique resource in its own right, consisting of both tangible and intangible qualities. Therefore we cannot secure an enduring resource of wilderness simply by applying traditional natural resource management to various biophysical resources of wilderness. Preserving the resource of wilderness requires that we protect the overall wilderness character of each area in the System.

Public Purposes of Wilderness

As discussed above, the purpose of the Wilderness Act is singular: to secure an enduring resource of Wilderness. People commonly confuse this with the “public purposes” of wilderness referred to in Sec. 4 of the Act. The title of Sec. 4 is “Use of Wilderness Areas.” Sec. 4(b) states that, “Except as otherwise provided in this Act, wilderness areas shall be devoted to the public purposes of recreational, scenic, scientific, educational, conservation, and historical use.”

These “public purposes” are not the purpose of the Act, they are the appropriate purposes for which the public may use Wilderness. These “public purposes” are allowable uses of Wilderness. However, they are not mandatory uses. These “public purposes” or uses do not take precedence over the singular purpose of the Act, which is to preserve an enduring resource of wilderness by preserving the Wilderness character of each area in the NWPS.

If any of the allowable public uses of Wilderness conflict with the preservation of an area’s Wilderness character, then protecting Wilderness character has priority. Since the “public purposes” are allowable but not mandatory uses, a Wilderness can be completely closed to one or all of these “public purposes” if such use would diminish or degrade key components of Wilderness character. For this reason, there are several Wildernesses that are completely closed year-round to any public entry, as well as some that are completely closed to the public for part of the year.

If the public uses were the purposes of the Act, then it would make no sense to close some areas to those uses. But Zahniser himself was emphatically clear on the secondary role of public uses in wilderness: “The purpose of the Wilderness Act is to preserve the wilderness character of the areas to be included in the wilderness system, not to establish any particular use.”

For example, although recreation is an allowable use, it must be conducted in a manner that is compatible with preserving Wilderness character. This means the use of motorized and mechanized equipment to maintain trails and other recreational facilities can rarely be justified in Wilderness because motorized use diminishes Wilderness character. Promoting easy or convenient trail use is not necessary for preservation of wilderness character and therefore does not justify incompatible methods of trail maintenance. The protection of Wilderness character must come first, ahead of any allowable public uses of wilderness.

Minimum Requirement

Section 4(c) of the Wilderness Act provides the basis for the concepts of “minimum requirement” and “minimum tool.” These concepts apply to agency administrative actions in wilderness, including actions undertaken by non-agency entities with authorization through a permit issued by the managing agency. Examples of administrative actions are trail construction and maintenance, wildlife management, and fire management activities. Examples of agency-authorized activities requiring a permit are scientific research, management of livestock grazing, and commercial outfitting and guiding. Together, the concepts of minimum requirement and minimum tool are used to determine the appropriateness of administrative actions in Wilderness.

Section 4(c) prohibits a variety of specific actions in wilderness because their presence, however temporary, is contrary to the meaning of Wilderness character:

PROHIBITION OF CERTAIN USES. Except as specifically provided for in this Act, and subject to existing private rights, there shall be no commercial enterprise and no permanent road within any wilderness area designated by this Act and except as necessary to meet minimum requirements for the administration of the area for the purpose of this Act (including measures required in emergencies involving the health and safety of persons within the area), there shall be no temporary road, no use of motor vehicles, motorized equipment or motorboats, no landing of aircraft, no other form of mechanical transport, and no structure or installation within any such area.

Section 4(c) explicitly prohibits two things in Wilderness, and also prohibits a number of other specific activities but makes two narrow exceptions for when these activities may be allowed. The two explicitly prohibited activities are commercial enterprise and permanent roads. The only exception to this prohibition is if there are prior existing rights that allow for these uses, such as a legal right-of-way.

The other generally prohibited activities in Sec. 4(c) include landing of aircraft, temporary roads, use of motor vehicles or mechanized transport, motorboats, motorized equipment, and placement of structures or installations. The Wilderness Act provides two very narrow exceptions for these generally prohibited activities, as described in the two steps discussed below.

The minimum requirement concept does not apply to the general public’s use of wilderness because the general public has no authority to engage in any of the prohibited activities listed in Sec. 4(c) of the Act.

Wilderness as a System

The 1964 Wilderness Act established the National Wilderness Preservation System, and directed all four land management agencies to manage wilderness in the same manner and according to the same principles and concepts as provided in that Act. Today, the NWPS is larger than our National Park System (83 million acres) and our National Wildlife Refuge System (92 million acres). Unlike these other two land protection Systems, however, the concepts and principles of the organic Act that established the NWPS have not been applied consistently across the System. This means that many of the qualities that the Wilderness Act sought to preserve are not being protected and are in fact declining and suffering degradation.

In order to achieve the Wilderness Act’s purpose to preserve an enduring resource of wilderness, it is imperative that the meaning and values of wilderness be upheld System-wide. Wilderness should be a recognizable resource, it should be managed according to the Wilderness Act’s intent that it be a place in contrast to civilization. Only by applying the Wilderness Act’s concepts and principles evenly across the System and to every new wilderness that is designated in the future will Wilderness continue to have any meaning as a unique resource in America.

Though each managing agency is governed by the Wilderness Act, they are left to draft up their own management policies and regulations. The resulting mish-mash of management styles and objectives results in a confusing and often ineffective stewardship regime. While some Wildernesses enjoy management commitment to the purpose and values of Wilderness, the protection of many if not most of our wildernesses fall through the cracks due to due to other managerial priorities and misunderstanding or apathy regarding the values and meaning of Wilderness.

Designating an area as Wilderness by law and on the map does not automatically protect it as Wilderness. It is critical that the meaning and purpose of wilderness be widely understood and respected by both the public, wilderness visitors, and those entrusted with an obligation to implement the spirit and intent of the Wilderness Act.

To learn more, read our Policy Guide and our Vision for Wilderness.

Photo: Jerome Walker

Contact Us

Wilderness Watch

P.O. Box 9175

Missoula, MT 59807

P: 406.542.2048

Press Inquiries: 406.542.2048 x2

E: wild@wildernesswatch.org

Minneapolis, MN Office

2833 43rd Avenue South

Minneapolis, MN 55406

P: 612.201.9266

Moscow, ID Office

P.O. Box 9765

Moscow, ID 83843