By Frank Keim

Thinking back...

deep

into the heart of these arctic mountains

known today as the Brooks Range,

I remember

the long windy solitude of the valley,

where gray river cobbles collide

with a braided maze of ancient caribou trails,

By Frank Keim

Thinking back...

deep

into the heart of these arctic mountains

known today as the Brooks Range,

I remember

the long windy solitude of the valley,

where gray river cobbles collide

with a braided maze of ancient caribou trails,

I hope the following paints a sunnier portrait of the desert.

I hope the following paints a sunnier portrait of the desert.

The Oregon Badlands Wilderness is a 29,000-acre protected area in the high desert administered by the Bureau of Land Management. The desert’s hardy flora roots itself into the land’s shield volcano, which came into being 80,000 years ago when a lava tube running underneath the ground sprung a leak. Lava oozing north, south, east, and west created the badlands.

The sandy, light colored soil that the raccoon prints are imbedded in comes from thousands of years of eroded lava. At various locations in the badlands, there are elevated volcanic rock formations—ships in the sagebrush sea—that allow for unobstructed views of the Cascade volcanoes to the west and the vast desert to the east.

By Jim Peek

I’ve seen quite a few cougars over the years, but the biggest one was in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness in Idaho.

My way to cool off from the spring semester at the University of Idaho was to borrow Maurice Hornocker’s two pack mules, saddle my horse, and have the agriculture school’s stock truckers take me to Selway Falls and drop me off. I would then ride the 50 or so miles to White Cap Creek. It was May, when the shrubs were in bloom and nobody else was in there.

I usually checked with the Forest Service about whether the trail was avalanched shut or if it was open. When they invariably told me it was impassible, I always went regardless and never dropped a pack.

By Kevin Proescholdt

This fall, my wife Jean and I visited Theodore Roosevelt National Park in western North Dakota. Though we had driven through the area on I-94 in the past, we had never explored the park, nor visited its designated Wildernesses. We had a wonderful time visiting and hiking in the park, and exploring the Theodore Roosevelt Wilderness.

We found that the National Park Service (NPS) itself does very little to highlight the Theodore Roosevelt Wilderness within the National Park, and it was very difficult to find information about the Wilderness from the NPS. That needs to change, but that situation also unfortunately reflects the NPS’s generally lackadaisical and cavalier attitude toward Wilderness across the nation.

By Shane Vlcek

I spent most of my adulthood in the western states of Idaho, Montana, and Oregon. Experiencing the backcountry was always something I looked forward to. But finding the opportunity and time to explore those sacred Wilderness places where true freedom is no longer in front of the next step or beyond the next ridgeline had always been a chance experience rather than a lifestyle.

By Kevin Proescholdt A recent AP story about a new report on the “recovery” of wolves at Isle Royale National Park in Lake Superior quoted me as saying, “We have felt and still believe that the National Park Service should not have intervened and set up this artificial population of wolves.”

A recent AP story about a new report on the “recovery” of wolves at Isle Royale National Park in Lake Superior quoted me as saying, “We have felt and still believe that the National Park Service should not have intervened and set up this artificial population of wolves.”

Why this stick-in-the-mud quote from an organization that defends wolves and Wilderness across the country in an otherwise positive story about wolves thriving on Isle Royale?

The short answer is the park’s official wilderness designation. In 1976, Congress designated about 99% of Isle Royale National Park—just over 132,000 acres—as the Isle Royale Wilderness. That welcomed designation provides the best and most permanent landscape protection for federal lands. But unlike the two-million-acre Yellowstone National Park—which unfortunately has not yet a single square inch of designated Wilderness—wilderness designation at Isle Royale also provides an additional layer of protection that argues against the meddling that the National Park Service (NPS) has done at Isle Royale.

The 1964 Wilderness Act established the National Wilderness Preservation System that now also includes the Isle Royale Wilderness. The main descriptor in the Wilderness Act is the word “untrammeled”. It was chosen very carefully by Wilderness Act author Howard Zahniser. Untrammeled doesn’t mean untrampled, untouched, or pristine, as some assume, but it means unmanipulated, unconfined, or unhindered. After designation, Wilderness must be allowed to evolve on its own terms without our manipulations, even if humans had damaged the landscape in the past or manipulated its ecosystem previously.

The Wilderness Act thus requires us to stop imposing our human desires or whims on wilderness landscapes, and to allow Wilderness to function without our manipulations and interferences. In Wilderness, we should let Nature call the shots, not us. In Wilderness, we humans must exercise humility and restraint, not meddle.

In 2018, the NPS decided to import more wolves to Isle Royale, since the “natural” wolf population had dwindled to only two inbred individuals. The NPS feared that without wolves, the large moose population would browse balsam fir down to the ground. The recent report celebrates the resurgence of the new, artificial wolf population to 31 individuals, and the moose population has declined to 967 from an estimated population of about 2,000 in 2019. The researchers claimed victory, even though in doing so they have transformed Isle Royale from a wild Wilderness to something more like a huge, manipulated outdoor zoo.

But what if the wolf reintroduction hadn’t happened, and we had allowed Nature to call the shots? Most likely the wolf population would have blinked out, and the large moose population would have eventually declined to some new level. But buried in the recent report was the interesting fact that for every moose recently killed by the new wolves, up to three more moose died of starvation—an indication that Nature would have reduced the moose population all on its own.

Should there be any wolves on Isle Royale? That should be for Nature to decide. One of the principles of island biogeography is that on islands, species come and species go over time, with some species blinking out and new ones arriving. At the turn of the twentieth century, for example, the main predator-prey relationship on Isle Royale was Canada lynx and woodland caribou. Both species are now long gone, with wolves only recently arriving on their own in the late 1940s. Should we bring all species that once existed there back to Isle Royale? Because this is designated Wilderness, we should let Nature call the shots. The NPS must learn to respect the Wilderness Act and stop the agency’s meddling on Isle Royale merely to prop up a now-fake predator-prey dynamic.

So let’s stop the manipulations at Isle Royale, and enjoy Isle Royale for what it is, not what we humans might want it to be. One manipulation today often means more manipulations in the future, particularly with climate change altering our natural landscapes. Even the NPS’s own modeling suggests that climate change may imperil the survival of moose on Isle Royale in the future. Will we then import an artificial population of moose to feed the artificial population of wolves?

Let’s all learn to respect Wilderness instead.

Kevin Proescholdt is Wilderness Watch's Conservation Director.

I recently wrote an op-ed calling the proposed “Protecting America’s Rock Climbing Act” (PARC Act) an imminent threat to Wilderness. In response, members of the Access Fund, the group behind the bill, have been contacting individual publishers, pressuring them to pull the piece. They’ve (wrongly) called it misleading and “fake news,” and some have even resorted to publicly attacking the character of individual editors. Fortunately, to my knowledge, only one publication—Adventure Journal—has caved, and many climbers have contacted me privately thanking me for the piece.

I have been litigating Wilderness issues, engaging agency decision-making, and studying the Wilderness Act and its regulations for over a decade—many of my colleagues have been doing this work for several decades. We see how statutes play out on the ground, long after they are passed, and we’ve also seen a recent explosion of recreation pressure in Wilderness, climbing included. The PARC Act will absolutely weaken the Wilderness Act and open the door to additional recreation pressures throughout the National Wilderness Preservation System.

Republican Representative Curtis from Utah, touting the proposed PARC Act, called outdoor recreation an “ever-growing industry” in his state, and his state is not alone. A recent Climbing article noted that overcrowded climbing areas throughout the country are pushing climbers farther into wilderness, creating environmental and wilderness character issues. In the same article, the Access Fund reports “exponential growth” in climbers over the last few decades—growing from the hundreds of thousands to roughly 8 million today.

The PARC Act itself was drafted in response to federal agencies trying to get a handle on escalating climbing impacts in Wilderness and trying to bring agency management into compliance with the Wilderness Act. In Joshua Tree, for example, where visitor use has more than doubled since 2000, “[t]he National Park Service estimates there could be as many as 20,000 bolts in the park; 30% are in wilderness.” Expressing concern about growing climbing pressures and trampled desert soil crusts and vegetation, the Park Service notified the public that it would be creating a new climbing management plan to better manage climbing in the Wilderness and comply with the Wilderness Act. It (accurately) noted that the Wilderness Act prohibits installations in Wilderness and that fixed climbing anchors are considered installations. Other agencies, like the Forest Service, have long held this position—the Park Service just started doing what was legally required of it all along.

The PARC Act would undermine these efforts and weaken the Wilderness Act by codifying “the placement, use, and maintenance of fixed anchors” as “allowable activities” in Wilderness.

Downplaying the problem, a few climbers argued that indiscriminate bolting and heavy use will not occur. This is conjecture, particularly given the rapid growth in climbing and given the PARC Act itself places no restrictions on anchor use in Wilderness. It kicks that can down the road to future agency guidance policies, which are not law and can be changed at any time. The PARC Act makes no distinction between rappelling anchors, bolted routes, discrete pitons, or indiscriminate bolting.

Our op-ed expressed serious concerns over the impact of the PARC Act on both the integrity of the Wilderness Act—our most protective public lands statute—and the National Wilderness Preservation System because, ultimately, it is the language of the statute that matters, not opinions on climbing practices or what already strained Wilderness administering agencies may or may not do through future policy. The law is what matters, and the PARC Act, if passed, will change the law across the entire National Wilderness Preservation System.

Over 40 conservation groups, the Forest Service, and the Park Service have opposed the bill.

Amendments to the bill, which the agencies have not endorsed, have made things worse by arguably mandating the maintenance of existing fixed anchors in Wilderness.

You can take a deeper dive into the issue through our Q & A here, and read more about why all of this matters here.

TAKE ACTION: Please urge your members of Congress to oppose the PARC Act as well as its Senate counterpart, S.873.

Dana Johnson is the Policy Director for Wilderness Watch.

By Kevin Proescholdt Wilderness Watch has recently sued the U.S. Forest Service in federal district court over the agency’s decades of failures to control commercial motorized towboats in the fabled Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) in Minnesota as required. We are now awaiting the judge’s ruling on our motion for a preliminary injunction.

Wilderness Watch has recently sued the U.S. Forest Service in federal district court over the agency’s decades of failures to control commercial motorized towboats in the fabled Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) in Minnesota as required. We are now awaiting the judge’s ruling on our motion for a preliminary injunction.

Wilderness Watch took the Forest Service to court because the agency has refused to limit commercial motorized towboat use in the Boundary Waters to levels that protect the wilderness, comply with law, and conform with the limits the Forest Service itself pledged to federal courts that it would maintain.

It’s important to keep in mind the special place the BWCAW holds in the National Wilderness Preservation System. It’s the only major lakeland wilderness in the nation, and people come from all over the world to paddle amid its natural beauty and to experience quietness and solitude away from the motorized intrusions of our civilized world. Congress designated the BWCAW as a wilderness to protect its wild character, and management of the area should always lead in that direction. Unfortunately, towboats have been a big exception to that policy.

These towboats in the Boundary Waters are commercially run motorboats that shuttle canoe parties to get a head start on other paddle parties or to avoid paddling long stretches of lake. Though called towboats, they actually carry canoes on overhead racks. The heaviest towboat traffic occurs on the Moose Lake Chain east of Ely and on Saganaga Lake at the end of the Gunflint Trail.

Nearly all towboat passengers are canoe parties, equipped to go on wilderness canoe trips. The current litigation does not affect any party’s BWCAW entry permit for 2023. Even if all motorized towboat use were to end, everyone with a permit would still be able to take their canoe trips this summer, with just perhaps a few extra hours of paddling needed on their first day.

In the litigation that followed the release of the 1993 BWCAW Management Plan, one issue challenged by wilderness organizations was the Forest Service’s move to pull the commercial towboats out of the regular motorboat limits. To settle that point of the litigation, the Forest Service pledged to the federal courts it would separately limit the amount of towboat use to the levels that occurred prior to the 1993 plan, which the agency said was 1,342 towboat trips per year across the entire BWCAW.

But the Forest Service never attempted to limit towboat usage to that level and instead allowed it to grow to excessive levels. Forest Service figures show it grew to 4,817 towboat trips in 2019, and 3,815 trips in 2020, making those towboat lakes into wilderness-sacrifice zones. Not surprisingly, the Forest Service now disavows the 1,342 figure, since it has allowed motorized towboat use to nearly triple in recent years.

Further complicating the Forest Service failures, the 1964 Wilderness Act contains a general prohibition on commercial enterprise in designated wildernesses. Commercial services are allowed, but they are limited to what is strictly “necessary.” The Forest Service has never conducted its required analysis to create a necessity-bound limit for towboats. After Wilderness Watch first sued the Forest Service on this issue in 2015, the agency promised to conduct such an assessment for commercial towboats by 2019, yet it still has not done so.

To some extent, this is not surprising. The Forest Service has shown its colors on this issue for decades. Congress intended with the 1978 BWCAW Act to terminate commercial towboats by 1984, as shown by statements in the Congressional Record, reporting in the press, and other sources. Prior to 1978, the Forest Service allowed towboats with unlimited-horsepower outboard motors. The 1978 law phased out the unlimited-horsepower outboards, believing that would end the commercial towboats. But towboaters discovered they could operate with 25-horsepower motors, and the Forest Service allowed towboats to continue, even though it was at odds with the intent of Congress.

After many years, it appears the Forest Service is still more interested in protecting commercial motorized towboats than in protecting the wilderness character of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, as Congress intended. We hope the federal court agrees that the Forest Service must abide by its own standards and limit towboats as required.

Kevin Proescholdt of Minneapolis serves as the conservation director for Wilderness Watch. He has worked to protect the BWCAW for nearly 50 years, guided wilderness canoe trips in the area for 10 years, helped pass the 1978 BWCAW Act through Congress and co-authored the definitive history of that effort: Troubled Waters: The Fight for the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderenss by briandjan607 via flickr.

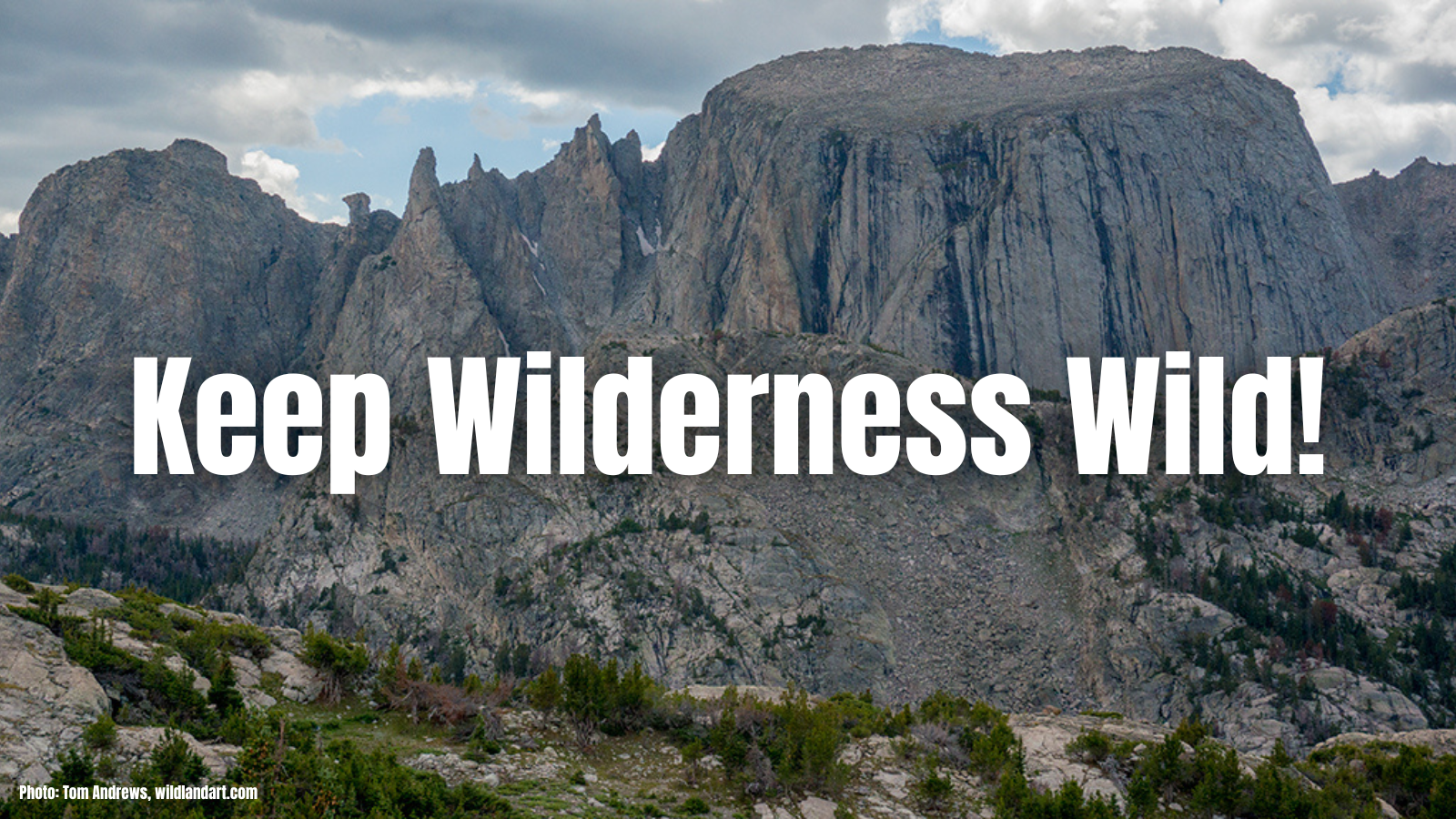

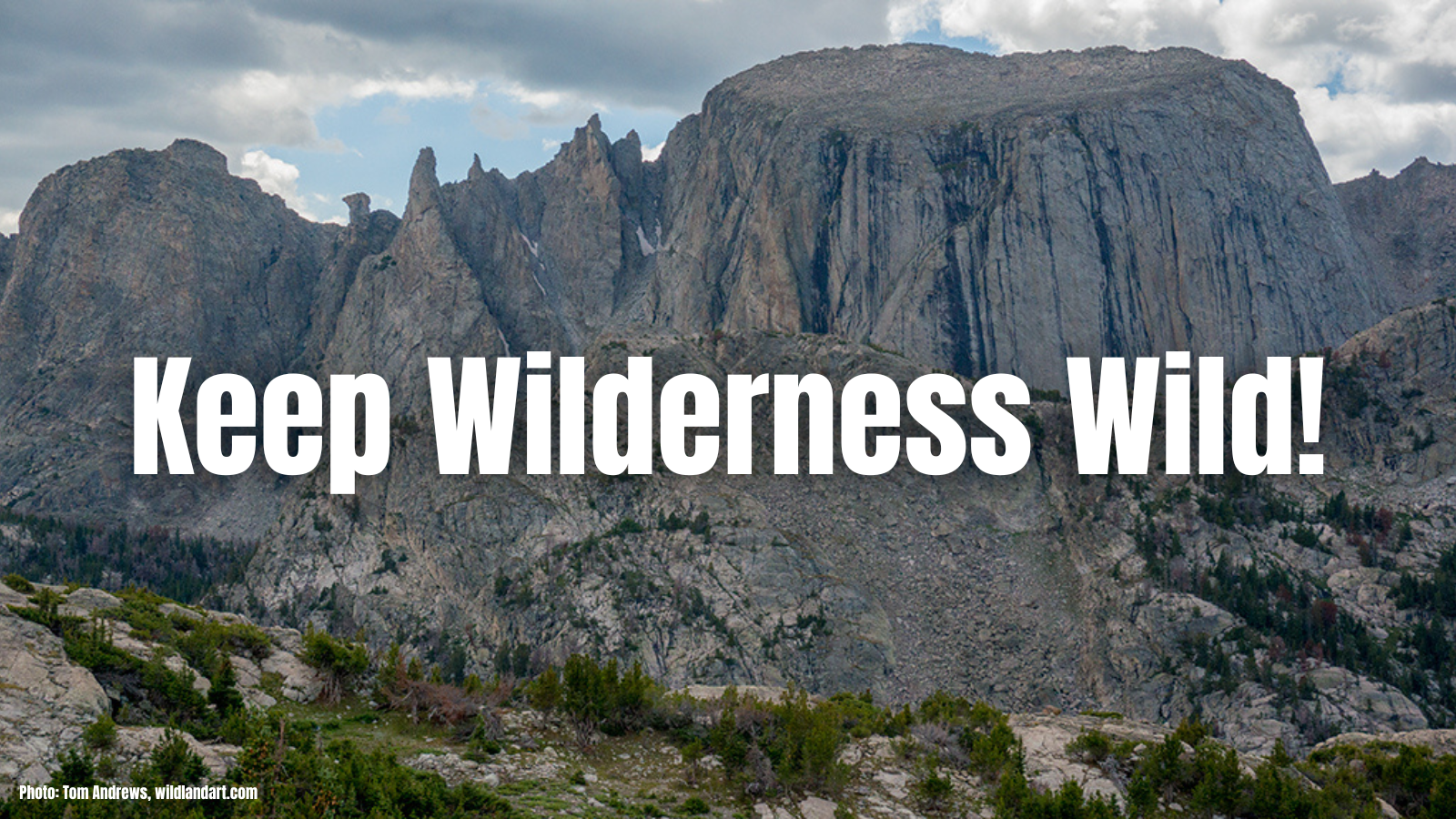

There are relentless pressures on the natural world at this moment, and right now, Congress has its attention on a bill that would compound those pressures in our most protected places. The boldly named “Protecting America’s Rock Climbing Act” (“PARC Act,” H.R. 1380) will allow climbers to drill permanent metal anchors into Wilderness mountainsides and cliffs, leaving visual evidence of human development and undoubtedly drawing more climbers to sensitive and remote locations. And the bill will weaken the landmark 1964 Wilderness Act—America’s most protective environmental law—to appease the climbing preferences of a small but vocal group of recreationists. It is the proverbial crack in the Wilderness Act’s armor and a harbinger of what’s to come. Wilderness Watch, along with over 40 other conservation groups, have written Congress to oppose the bill and protect the tiny bit of wild we’ve allowed to remain.

There are relentless pressures on the natural world at this moment, and right now, Congress has its attention on a bill that would compound those pressures in our most protected places. The boldly named “Protecting America’s Rock Climbing Act” (“PARC Act,” H.R. 1380) will allow climbers to drill permanent metal anchors into Wilderness mountainsides and cliffs, leaving visual evidence of human development and undoubtedly drawing more climbers to sensitive and remote locations. And the bill will weaken the landmark 1964 Wilderness Act—America’s most protective environmental law—to appease the climbing preferences of a small but vocal group of recreationists. It is the proverbial crack in the Wilderness Act’s armor and a harbinger of what’s to come. Wilderness Watch, along with over 40 other conservation groups, have written Congress to oppose the bill and protect the tiny bit of wild we’ve allowed to remain.

You can help keep Wilderness wild by writing your members of Congress and urging them to oppose H.R. 1380.

Dana Johnson is the Policy Director for Wilderness Watch.

by Harriet Greene

My daughter and I drove south towards the turnoff, then seventeen miles on gravel to the trailhead. A pack trip was leaving and the wrangler, spitting a wad of tobacco, told us about “one of the best campsites” where we were headed. The trail climbed through a grove of aspens, stayed high on a sage-covered slope above Upper New Fork Lake, and we crossed into the Bridger Wilderness at 3.4 miles. Ah-h-h!

My daughter and I drove south towards the turnoff, then seventeen miles on gravel to the trailhead. A pack trip was leaving and the wrangler, spitting a wad of tobacco, told us about “one of the best campsites” where we were headed. The trail climbed through a grove of aspens, stayed high on a sage-covered slope above Upper New Fork Lake, and we crossed into the Bridger Wilderness at 3.4 miles. Ah-h-h!

After a seven-mile climb into the steep New Fork Canyon and two tricky river crossings, we ascended to a meadow, exhausted and desperate for a site. Fording the river again to a heavily-used area with a lot of horse manure, probably the spot the wrangler had mentioned, we moved far enough away, pitched our tent and cooked dinner just as it started to drizzle.

By Brett Haverstick

I was off work and at the trailhead by 6:00 p.m. I estimated that I had about three-and-a-half hours of daylight to hike the eight miles to Bass Lake on the Montana side of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness. I wasn’t in the best backpacking shape, but I figured I could still knock out the miles and the 3,500 ft. elevation gain before it was completely dark. I hadn’t backpacked into the Selway—Bitterroot, my favorite Wilderness, since last autumn.

I was off work and at the trailhead by 6:00 p.m. I estimated that I had about three-and-a-half hours of daylight to hike the eight miles to Bass Lake on the Montana side of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness. I wasn’t in the best backpacking shape, but I figured I could still knock out the miles and the 3,500 ft. elevation gain before it was completely dark. I hadn’t backpacked into the Selway—Bitterroot, my favorite Wilderness, since last autumn.

By Phil Knight

What good is designated wilderness? Are the Lee Metcalf or the Absaroka Beartooth “wasted lands” because people can’t just go do whatever they want there?

What good is designated wilderness? Are the Lee Metcalf or the Absaroka Beartooth “wasted lands” because people can’t just go do whatever they want there?

I am currently (temporarily) disabled from a fall and cannot walk unassisted. There will be no wilderness trips for me this summer.

By Michael Lipsky

For many years I had wanted to return to the Elysian Fields, an off-trail backcountry area of trackless meadows in the Mount Rainier Wilderness within Mount Rainier National Park. The opportunity arose when I joined my son, Josh, and three of his friends on a backpacking trip a few years after they graduated from college.

For many years I had wanted to return to the Elysian Fields, an off-trail backcountry area of trackless meadows in the Mount Rainier Wilderness within Mount Rainier National Park. The opportunity arose when I joined my son, Josh, and three of his friends on a backpacking trip a few years after they graduated from college.

by Howie Wolke

The Colorado Plateau of eastern and southern Utah is a unique landscape of colorful sedimentary rocks and mesas dissected by spectacular canyons of the Green and Colorado River systems. And, despite a long history of ranching, mining and the associated dirt road network fragmenting the outback, much of this spectacular realm remains roadless and wild.

In 2019, the John D. Dingel Conservation Act designated 17 new Wilderness areas in Utah’s canyon country, totaling 663,000 acres— a formidable accomplishment given Utah’s political culture. The bill also protected 3 segments of the Green River under the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. Fourteen of the new Wildernesses are within the rugged San Rafael Swell, which many consider to be a potential new national park. Two new Wildernesses are in the Desolation Canyon-Book Cliffs area, and the act also protected wildlands on the east side of the Green River in Labyrinth Canyon.

The 143,000-acre Desolation Canyon Wilderness is the largest new Wilderness. The Desolation Canyon country (“Deso”) is remarkable even by Utah standards. The Green River slices a 5,000-foot deep gorge through colorful layered sediments. But wilderness isn’t just about scenery. Deso harbors unusual habitat diversity, ranging from wetlands and riparian cottonwood forests to Colorado Plateau Desert of sagebrush and saltbush, to pinyonjuniper woodlands and even stands of Douglas-fir, true fir, spruce and aspen at the highest elevations. This habitat diversity, along with the area’s large size, supports unusually high biodiversity, especially for wildlife. The obvious critters are mule deer, elk, bison, black bear, bighorn sheep, coyote and mountain lion, but there are also midget faded rattlesnakes, tarantulas, ferruginous hawks, both eagle species, peregrine falcon, long-billed curlew, white-faced ibis plus wild turkey, lots of waterfowl, beaver and much more. There are 3 endangered fish species, in addition to the Green’s tasty catfish.

For us two-legged primates, Deso is known as one of the premiere wilderness float trips in North America, with over 100 miles of floatable wild river. In fact, a September 1982 80-mile Deso journey was my first of many ensuing wilderness river adventures.

The recently designated Wildernesses in Utah represent progress, yes, but it’s just a start. Take Deso, for instance. Its 143,000 acres of Wilderness along and adjacent to the west shore of the Green River represent much less than half of the roadless wildland. There are roughly 500,000 acres of contiguous BLM-administered lands that could be included in the Wilderness, including a gentle 30-mile section of the Green River upstream from the canyon, a rich habitat of riparian wetlands and high desert benches, known for its diverse avifauna including herons, ibises and waterfowl. The ecological values of this river section are particularly outstanding. Downstream, while the official Wilderness protects lands only in the southern end of the canyon on the west side of the river, 165,000 acres of Desolation Canyon’s east side are managed as wilderness by the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation. In fact, a holistic view of the Desolation Canyon country recognizes a roadless wildland of about 860,000 acres. Close a handful of “cherry-stemmed” dirt roads plus the four-wheel drive dirt road that separates Deso from the adjacent Turtle Canyon Wilderness, and the Desolation wildland grows to nearly a million unbroken acres!

In addition to incomplete designations, threats to the new Wilderness units and contiguous wildlands abound. In a region that did not evolve with large herds of hoofed mammals such as bison, cattle chomp the uplands, destroying fragile biotic crusts, and they pollute and physically demolish riparian habitats. Mining and oil/gas development threaten roadless lands adjacent to the Wilderness, and illegal off-road vehicle abusers—including mountain bikers—scar both the Wilderness and adjacent roadless areas. In addition, the BLM currently allows motors in both Desolation and Labyrinth Canyons. Backcountry airstrips are another insult.

Of course, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is often called the “Bureau of Livestock and Mining”, catering shamelessly to those two industries plus mechanized off-roaders. Recently, the agency initiated a planning process that lumps the Dingel Act’s new Wilderness areas together with developed BLM-administered multiple (ab) use lands. Instead, each Wilderness area or Wilderness cluster should merit its own wilderness stewardship plan. In the United States, Wilderness is the highest level of land protection, surpassing even that of national parks, unless the park includes designated Wilderness. Wilderness is the antithesis of civilization’s unrelenting quest to dam, pave, bulldoze, fence, graze, log, dig, drill, subdivide, mechanize, urbanize and otherwise fragment nature’s original landscape. Wilderness is nature’s original landscape, and as the growing human population continues to obliterate wild nature, wild nature will continue to become both harder to protect and more fundamentally important.

The preliminary scoping period for public comments on the BLM planning process ended in January. Remember, though, that we taxpayers employ federal agency personnel, including BLM employees. They work for us, not just for ranchers and miners! And by law, they must consider public comments, even outside of timelines delineated by a particular planning process. Here is a sample of what the BLM needs to hear:

As mentioned, the BLM should create area specific wilderness stewardship plans for each designated Wilderness or Wilderness cluster. For example, there should be one stewardship plan for Deso and the Turtle Canyon Wilderness plus the Green’s three designated wild and scenic river segments. Plans should clearly specify that Wilderness areas must be managed primarily to protect wilderness character—as the 1964 Wilderness Act mandates! Plans should also prioritize wildlife, native species and overall wildness rather than trying to mollify various user groups.

The BLM should also maintain the roadless/undeveloped character of unprotected roadless areas, and should recommend them for Wilderness designation.

In addition, vacant livestock allotments should be permanently closed, and the BLM should amend its resource management plans to curtail livestock grazing where it is damaging natural ecosystems, which is nearly everywhere in these arid environments. Then they should remove unnecessary grazing infrastructure. Motor boats are an insult to Desolation and Labyrinth Canyons and should be banned. So should aircraft landings in Wilderness. In fact, the BLM should eliminate all mechanized use of Wilderness and roadless potential wilderness within the planning area. And finally, closing off and reclaiming cherry-stemmed road intrusions would enlarge Wilderness, and create more defensible wilderness boundaries plus more ecologically functional Wilderness with less edge and more secure interior habitat.

Utah’s remaining wild canyon country is a gift. That much of it still remains wild is a function of luck, topography and the hard work of conservationists in Utah and elsewhere. Let’s give future generations of all creatures the enduring gift of perpetual wildness. For there is no greater quest than that to protect and restore truly wild wilderness.

------------------

Howie Wolke is a retired wilderness guide/outfitter from southern Montana near Yellowstone National Park. He is on the Wilderness Watch board of directors and has also served two terms as president of the organization. He lives with his wife Marilyn Olsen and their dog Rio in southern Montana near Yellowstone National Park.

Photo: Bob Wick, BLM

Secretary Haaland and the Izembek Refuge

By Fran Mauer

Nearly forty-two years ago, Congress passed the greatest public land conservation legislation in American history -- the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA). After prolonged discussions among State, Alaska Native, development, federal and conservation interests, a compromise on ANILCA was reached.

Reflecting this balanced approach, and in response to the strong national sentiment to protect these lands and the subsistence resources they sustain, the U.S. Senate voted 78-14 to approve ANILCA. The vote was bipartisan.

For Alaska and Alaskans, the extraordinary lands protected by ANILCA have been crucial in supporting subsistence, conservation, tourism, ecosystem services and more.

Unfortunately, since passage of this unprecedented conservation law, there have been efforts to undermine its purposes and integrity.

A primary tactic by opponents has been to misapply the land exchange provisions of ANILCA to transfer ownership of lands out of protected areas in order to achieve development purposes, contrary to the purposes of ANILCA. The first such effort came in 1983 when the Reagan administration attempted to exchange lands for an off-shore oil exploration facility in the Saint Matthew Island National Wildlife Refuge Wilderness. This illegal exchange was nullified in court.

Another effort to promote development in conservation areas occurred when the Bush administration pursued a land exchange in the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge, for oil exploration and development. Deeply concerned about the impacts this would have on subsistence and wildlife, village residents of the Yukon Flats objected. This exchange was subsequently dropped during the Obama-Biden administration.

Now, Secretary Haaland is being asked to support a land exchange that would allow a road to be built across the Izembek National Wildlife Refuge Wilderness that is virtually identical to one that was rejected by Secretary Jewell in the Obama/Biden Administration.

After extensive public review and comment, Secretary Jewell determined that the road would have profound, negative impacts on the wildlife, subsistence values and wilderness values of the Refuge, including to birds that migrate to Izembek from the Yukon Delta and other areas of northern Alaska, upon which Alaska Natives who live in Western Alaska rely.

Regarding alternatives to the road, the US Corps of Engineers completed an evaluation several years ago, finding that a seaworthy ferry, break-water and an improved dock at Cold Bay would be effective. It has also been pointed out that during periods of harsh weather a road would be impossible to travel under any circumstances including medical evacuations. Especially now, given increased funding for infrastructure projects, building a breakwater and improved dock at Cold Bay is a much better solution.

Despite this thorough analysis, the Trump Administration pursued a road. The first attempted Izembek land exchange by the Trump administration, which had no public comment period or serious study, was struck down in our Alaska District Court.

Before Secretary Haaland is yet another Trump Administration land exchange, which was also finalized with no public input. Like the other land exchange proposals, this would seriously harm wildlife and subsistence resources.

As Secretary of Interior, Haaland’s primary responsibility in this situation is to protect the integrity of Izembek National Wildlife Refuge and the important role it plays in support of sustainable subsistence uses over a vast area of western and northern Alaska. She is also responsible for fulfilling the mandates of ANILCA, which Secretary Bernhardt clearly violated.

Secretary Haaland should not become the first Secretary in history to allow a road to be built through designated Wilderness, which also harms subsistence. Much better alternatives exist.

For more information, see the following:

What is Wilderness Without its Wolves?

By Franz Camenzind

For millennia, wolves have occupied nearly all the lands now designated as Wilderness in the western US, with the exception of coastal California. Yet today, fewer than two score of the approximately 540 Wildernesses west of the 100th meridian (not including Alaska’s 48) can claim some number of wolves as residents and only a dozen or so harbor wolves in numbers sufficient to be considered sustainable—in either the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, Central Idaho Wildlands or Montana’s Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem. Arguably, the long-term sustainability of wolves in other Wilderness areas is at risk due to the limited security provided by those smaller, often isolated landscapes.

The Wilderness Act defines Wilderness as a place where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by humankind, retains its primeval character and where natural conditions are preserved. Simply stated, Wilderness is meant to exist with minimal human interference. Yet within the vast majority of Wilderness areas, the wolf, the apex species with profound ecosystem influence, is now absent—an absence due entirely to the relentless killing by humankind.

We need look no farther than Yellowstone National Park to witness the influence wolves have on an ecosystem. The park’s wolves were exterminated by the early 1900s, ostensibly to protect the park’s favored elk herds. What followed was not surprising—an overabundance of elk which led to deleterious impacts to vegetation, particularly lower elevation riparian and willow communities.

Since the reintroduction of wolves to the park in the mid-1990s, elk numbers have dropped to levels most ecologists agree resemble something near carrying capacity. Similarly, park wolf numbers stabilized around 100, after initial highs of 150-170. With the wolf’s return, the park ecosystem is showing signs of reaching a dynamic equilibrium beneficial to all components. It’s not an exaggeration to say that wolves were instrumental in returning the park’s wildlands nearer to their primeval conditions.

Wolves hold apex status, in part, because of their far-ranging hunting behavior. Yellowstone-area wolf packs hunt in territories ranging from 185-310 square miles. Besides being smaller, the Yellowstone elk herd is more dispersed and spends less time in the lower elevation meadows and riparian-willow communities.

Most ecologists agree that the wolf’s collective impact on elk is contributing to the resurgence of the willow communities, which in turn is witnessing an increase in avian biodiversity and density. The revitalization of Yellowstone’s northern range willow communities has also enabled an increase in the beaver population, leading to positive changes to stream ecology, thus benefitting aquatic invertebrates and the fisheries.

Many of the ecological changes brought about by the wolf’s return may take years if not decades to recognize and fully understand. But one thing is clear, today’s Yellowstone and the Wildernesses harboring robust wolf populations more closely resemble their primeval character than those lacking wolves. Wolves may just be nature’s best wilderness stewards.

Three states now account for the majority of the west’s wolves: Idaho (1,556), Montana (1,220) and Wyoming (347). Another 351 are tallied for Washington (178) and Oregon (173). Mexican Gray Wolves occur in two states: New Mexico (114) and Arizona (72). Combined, approximately 3,660 wolves currently reside west of the 100th meridian—a number that pales to the 250,000 to 2 million estimated to have resided in the entire United States before the European invasion. However, the current numbers are better than the few dozen residing in northwest Montana three decades ago, which were a result of wolves immigrating from Canada.

Today’s bad news is that wolves in Idaho and Montana are once again facing the vigilante actions of the 1800s. Both state legislatures recently passed draconian legislation with the stated objective of reducing wolf numbers to near 150—the number at which the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) will take over wolf management as per the states’ wolf management agreements in effect since Endangered Species Act protections were taken away from wolves.

The new legislation authorizes the state commissions to allow wolf-killing by pretty much any means imaginable: the use of traps and snares, unlimited quotas, extended hunting and trapping seasons, and in Idaho, night time hunting, aerial gunning and killing pups in dens. Idaho also designated $200,000 dollars to “cover expenses incurred” by private individuals while killing wolves—essentially imposing a bounty on wolves.

Idaho’s and Montana’s aggressive wolf-killing legislation has been temporarily dampened a bit by the states’ wildlife commissions which have some leeway when setting annual wolf hunting and trapping regulations. For instance, this season, Montana is limiting the open-ended quotas written into their legislation. But the intent and goals remain unchanged—it may just take a few more years to achieve those goals. Ironically, that means more wolves will be killed because each year the survivors will produce young, thus replenishing their numbers, resulting in “a need” to kill more wolves to reach the 150 goal.

State wildlife agencies manage wolves by the numbers, ignoring the fact that wolves are one of the most social species on the planet, and function and survive not as individuals, but as members of highly structured packs. Consequently, intense, random killing can cause packs to break up, resulting in diminished hunting efficiency and pushing wolves toward easier prey, such as livestock.

Today, wolves and the wilderness ecosystems they inhabit are imminently threatened by these irresponsible state efforts to kill upwards of 90 percent of their wolf populations, including within Wilderness. A weakened or removed apex species inevitably results in a weakened ecological system. If this barbaric killing is allowed to proceed, ecosystem function and wilderness protection will be pushed back decades.

Wilderness Watch continues to fight for Wilderness and its wolves. On December 6, Wilderness Watch and a dozen allies filed a lawsuit and a motion for a temporary restraining order/preliminary injunction against the State of Idaho over its barbaric new wolf-killing laws. This followed a June 2021 Notice of Intent to sue Idaho and Montana for their new anti-wolf statues. We’ve petitioned the US Department of Agriculture to promulgate rules or issue closure orders preventing certain killing methods, hired killers, and paying bounties in Wilderness. Wilderness Watch also joined a petition authored by Western Watersheds Project to relist wolves under the Endangered Species Act in light of the new, aggressive wolf-killing statutes. In response, the US Fish and Wildlife Service announced that it will undertake a status review of the gray wolf over the next 12 months.

A Wilderness denied of its wolves is a wounded Wilderness. If wolves can’t be allowed live in Wilderness, where can they live? Wilderness Watch will continue to do all it can to protect this critical, symbiotic relationship and the ecological integrity of Wilderness itself.

Franz Camenzind is a wildlife biologist turned filmmaker and environmental activist who recently retired from the WW Board after serving 6 years.

By Frank Keim

We’re camped on the Hulahula River,

and after dinner

on a balmy night

five of us marched like caribou

single file

upriver

along a narrow animal trail

to a tall pingo

sculpted long ago from ancient ice melt,

By Brett Haverstick

Marty met us at the Bear Creek Trailhead at 9 a.m. We left my car in the lot, and she shuttled us over to Blodgett. Tim and I unloaded our packs, and went over our itinerary one last time. We expected to be back at Bear Creek in 5-6 days and then drive my car home.

Marty met us at the Bear Creek Trailhead at 9 a.m. We left my car in the lot, and she shuttled us over to Blodgett. Tim and I unloaded our packs, and went over our itinerary one last time. We expected to be back at Bear Creek in 5-6 days and then drive my car home.

by Howie Wolke

Back in the 1980’s, Dave Foreman and I compiled The Big Outside, A Descriptive Inventory of the Remaining Big Wilderness Areas of the United States (Harmony Books, 1989). The primary purpose was to accurately depict the true extent of each large roadless area in the contiguous 48 states, defining “large” as 100,000 acres or more in the West, with a 50,000 acre minimum for the East. We defined roadless areas as physical entities delineated by the location of roads and other intrusions that actually interrupt the flow of wildness.

So we mapped what was literally roadless and wild on the ground. We did not rely on agency inventories, because relying on federal agency inventories limits one to what the agencies have inventoried. Agency “roadless area” inventories are notoriously incomplete and often follow political demarcations such as state and county lines, national forest and BLM district boundaries, and isolated sections of state or private land. Moreover, agencies frequently gerrymandered “official” roadless area boundaries to exclude big chunks of wild country in order to facilitate plans for logging, mining, oil wells, off-road vehicle routes, water projects, livestock developments and so on. In other words, for a variety of reasons, many big contiguous chunks of roadless wilderness were and are divided into different administrative units, masking the true extent of the wildland.

Therefore, we hoped that by providing a comprehensive accurate inventory that clearly depicts the true extent of each big roadless area on the ground, regardless of political boundaries or considerations, conservationists would be more likely to develop and promote bigger, more holistic proposals for additions to the National Wilderness Preservation System.

Here’s an example of one inventoried big roadless area: we called it the “South Absaroka” wildland in northwest Wyoming. The Big Outside inventoried this area as the sixth largest unbroken wildland in the lower 48 states, at 2,190,000 acres. We also discovered and noted that deep within the South Absaroka was the most distant point from a road in the lower 48 states, 21 miles, just outside the southeast corner of Yellowstone. At the time of our inventory, the South Absaroka included the 704,000-acre Washakie Wilderness on the Shoshone National Forest, the 585,000-acre Teton Wilderness on the Bridger-Teton Forest, 483,000 acres of roadless backcountry in the southeastern quadrant of Yellowstone, 350,000 acres of unprotected roadless areas on both the Shoshone and Bridger-Teton National Forests, 60,000 roadless acres on the Wind River Indian Reservation, and about 10,000 acres of undeveloped state and private lands that abut national forest boundaries.

But because the South Absaroka is thus subdivided on paper into various named and un-named units, the true size and value of the area is obscured. To recognize the South Absaroka in the holistic sense is to recognize a 2,190,000-acre unbroken wildland, not just its various parts. Thus, the 350,000 acres of unprotected national forest roadless areas assume even greater importance than they would were they to stand alone. Same goes for the 483,000 acres of unprotected Yellowstone backcountry. That’s because the ecological value of wilderness increases with size. When it comes to wilderness, size matters. There are many reasons why.

For one thing, big chunks of wild country retain species and subspecies (biodiversity) better than small wildlands. Connectivity also increases the effective size of a wildland. Small isolated habitats lose species due to inbreeding depression and genetic drift in small isolated populations. Also, small isolated habitats and populations are vulnerable to demographic and environmental upheavals. The rate of species loss in small isolate (“island”) habitats can actually be calculated, as has been shown by E.O. Wilson and other ecologists. Many species simply won’t or can’t successfully cross roads, fences, reservoirs, off-road vehicle routes, power corridors, subdivisions, clear-cuts, oil fields, border walls and other developments that effectively create habitat islands of isolated populations. Habitat fragmentation is the enemy of biodiversity, and is rampant on our public lands. For example, the U.S. Forest Service has built a 400,000 mile-plus road network crisscrossing the public forests, not including state, county and other federal rights of way! You might say that the Forest Service and the BLM are primarily in the habitat fragmentation business, though they euphemistically call it “multiple use”.

Big protected Wilderness is a hedge against habitat fragmentation. Big wilderness also protects wilderness-dependent species such as grizzly, lynx and wolverine. It is well documented that large carnivores need big chunks of habitat because their populations are necessarily thinly spread over the landscape. Big carnivores are often “keystone species”, crucial to healthy ecosystem function.

For example, in the eastern U.S. the lack of large carnivores and the resulting explosion of whitetail deer in fragmented forests has damaged the eastern deciduous forest biome’s vegetation. Also, the recent resurgence of quaking aspen in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is partly a result of large carnivore recovery, mainly wolves, grizzlies and mountain lions – but the recovery is now jeopardized by various state plans to dramatically reduce wolf populations. Before wolf reintroduction, there were way too many elk browsing aspen seedlings and saplings (increased wildfire, beginning in 1988, has also stimulated quaking aspen growth). With the comeback of wolves and other big carnivores, elk numbers are down and aspens are coming back. So are willows, mostly for the same reasons. With more aspen and willow, beaver populations have increased, creating wetland habitats for various species of birds and other animals.

Big wilderness protects a greater variety of habitats than do small protected units, and greater habitat variety equals greater biodiversity. In addition, by protecting habitats along both elevational and latitudinal gradients, big wilds provide room for species to migrate in response to climate change. Big wilderness is a hedge against exotic weed infestations, which tend to explode in heavily managed roaded multiple use landscapes. Small isolated wildlands are often similarly infested, because of their proximity to roaded areas.

Big wilderness protects seasonal migratory routes better than small fragmented areas.

Big wilderness is also, obviously, our best opportunity for real solitude, an increasingly endangered value in this over-crowded world. Because deep backcountry is less crowded than areas easily accessible by road, resource damage is minimized. So there’s less need for agencies to regulate user numbers or to otherwise impose regulations. Fewer regulations means more freedom, another increasingly rare wilderness value.

Size facilitates good wilderness stewardship in other ways, too. Big wilderness is self-protecting, its core protected from human malfeasance by its remoteness. The armies of logging, mining, poaching, littering, off-road vehicle abuse, livestock trespass, arson and even illegal agency construction projects all are facilitated by roads. The insatiable agency compulsion to manipulate vegetation – especially in the Forest Service and BLM -- is also facilitated by proximity to roads. In big wilderness, illegal attempts to manipulate, tame, poison, construct, modify, and bulldoze are countered by the simple impracticality of implementing such mischief many miles from the nearest road. In other words, bigness increases the core to edge ratio of a wildland, and the edges, along and near roads, are where most human-induced mischief occurs.

Of course, size is self-protecting only when Congress doesn’t legislate special provisions that allow for destructive activities otherwise prohibited in wilderness. The biggest designated wilderness in the lower 48 states, the Frank Church River of No Return in central Idaho, includes a hodgepodge of legislatively grandfathered airstrips, jetboats, and private structures. Not to mention severe abuses by river and horse outfitters, to which the Forest Service invariably turns a blind eye.

Wildland Edge Effect is not just an inherent problem with small areas, but the shape of a wildland also has ecological ramifications. Excluding corridors from wilderness proposals for off-road vehicle use – including mountain bikes -- and excluding big chunks of wild country in order to mollify special interests such as loggers, oil drillers or ranchers results in wilderness boundaries that are irregularly shaped, like an amoeba, with low core to edge ratios. “Cherry stem” exclusions that dead-end deep within surrounding wilderness lands likewise produce more edge. Again, when remoteness is lacking, ecosystem integrity declines.

Here’s another huge reason for big wilderness: it allows for natural landscape processes. Natural predator/prey relationships, especially those that entail large carnivores are an obvious example (see above). And similar to predation, natural disturbance regimes such as wildfire, flood, blowdown and native insect outbreaks fuel the fires of evolution by weeding out those that are unfit to survive. The Wilderness Act defines wilderness in part as “untrammeled”, meaning uncontrolled or unregulated. Wild, not tamed. Most of these processes require big wilderness. For example, large carnivores simply can’t survive in tiny wilds. And it is difficult to allow natural wildfire to thrive in small wildlands adjacent to homes, towns, commercial logging areas and other facets of civilization.

When we researched The Big Outside, Dave and I were excited to discover that many chunks of roadless wildernesses were actually much larger than advertised. We had hoped that by inventorying the actual wildland entity as it existed on the ground, our project would inspire conservation groups to propose wildernesses designations that reflected the full wildland entity – or to at least begin a campaign from a stronger, less compromised position. We also suggested in numerous situations areas where roads could be closed, reclaimed and included in designated wilderness in order to create more holistic boundaries with less edge. But apparently, few of our conservation colleagues paid attention.

And therein lies the crux of the matter. Three decades later, too many conservation groups still begin the political process with parred down compromised wilderness proposals that are destined to grow even smaller as the political system inevitably slices and dices away at ecological wholeness. And unfortunately, the “big greens” such as The Wilderness Society (TWS) and some of their regional satellites – the Greater Yellowstone Coalition and the Montana Wilderness Association, for example – are leading the charge toward small edge-dominated “wilderness”.

In a nutshell, the template is this: Collaborate with local wilderness opponents and eliminate from the “wilderness” proposal most or all of the controversial areas so that mountain bikers, snowmobilers, loggers, oil drillers, ranchers and other wilderness opponents are mollified. Then take your emaciated proposal to the appropriate agency and to Congress. I actually watched one employee of The Wilderness Society give a seminar in which he proudly described the exact process that I just outlined.

Earlier, I mentioned special provisions that mar the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness. Various special provisions are often added to these weak “wilderness” bills to further appease opponents. Special provisions undercut both the letter and the spirit of the Wilderness Act by allowing activities in wilderness that are otherwise prohibited. In addition to airstrips and motorboats, special grazing privileges, water projects, ATV use for ranchers and other affronts to wilderness are often added to bills to make the so-called “wilderness” legislation even more palatable to otherwise anti-wilderness interests. Some wilderness bills even have special provisions to control natural wildfire, including fuel-breaks and logging in the name of “fuel reduction”. Special provisions for wildlife management include “guzzlers” to artificially inflate game numbers in arid landscapes, and provisions for implementing predator control. Remember, wilderness is supposed to be “untrammeled”, which means wild and unmanipulated by human whims.

With all of these enervated “wilderness” proposals, Marshall, Leopold, Murie, Zahniser, Brandborg and other wilderness visionaries spin in their graves. So does old Cactus Ed.

There are many examples of wilderness designations that facilitate habitat fragmentation, edge effect and mechanized recreation at the expense of ecosystem integrity. The former 545,000 acre (inventoried roadless acreage from The Big Outside) Boulder-White Clouds Roadless Area in south-central Idaho is one example. It was first whittled down and then sliced into two separate “wilderness” units by Congress, in order to create a non-wilderness mountain bike and motorcycle corridor. This dramatically decreased the core to edge ratio, slicing a big chunk of unbroken wild country in two.

In my home neck of the woods, the 575,000-acre Gallatin Range roadless area in northwest Wyoming and southern Montana includes 325,000 unbroken roadless acres in the northwest corner of Yellowstone National Park plus 250,000 acres of contiguous wilds to the north on the Custer-Gallatin National Forest. The Gallatins are an unbroken roadless wildland extending from West Yellowstone nearly to Bozeman, encompassing some of the richest mountain wildlife habitats in North America.

The so-called “Gallatin Forest Partnership” (GFP) was an ill-advised collaboration with wilderness opponents that intentionally excluded all of the less compromising conservation groups. The Wilderness Society, the Greater Yellowstone Coalition and the Montana Wilderness Association (now called “Wild Montana” without the word “wilderness” in its name) were the three main “conservation groups” responsible for this debacle. After most of the popular snow-machine and mountain biking areas were cut, GFP proposed 100,000 acres of mostly high altitude “wilderness on the rocks” out of 250,000 roadless acres in the Gallatins north of Yellowstone. Sadly, the best wildlife habitats in the Gallatins – especially the Porcupine and Buffalo Horn drainages – were excluded from wilderness consideration. Porcupine and Buffalo Horn, by the way, also form the crucial wildlife link between Yellowstone and the northern Gallatins and wildlands further to the north. Fortunately, Congress has not yet acted on the GFP plan.

Of course, these public lands are a legacy for all Americans, not just local “stakeholders”. That is another basic problem with all of the locally-based special interest “collaborations”. Most of the American public is excluded from the decision-making.

In my opinion, many of the larger conservation groups have lost their way, populated nowadays by careerists for whom wilderness is just one of many worthy causes on a varied career track. They view wilderness as one of many land use options rather than the fundamental basis for life on Earth, for 3.5 billion years of organic evolution. Political expediency prevails. The mentality is to pass truncated “wilderness” bills at all cost, nearly always through collaboration with traditional opponents. Avoid enmity and discord. And let’s face it. The big foundations, such as Pew, for example, expect collaboration and compromise. Follow the money and forget about biodiversity, wildlife and the value of big uncompromised holistic wilderness.

Nonetheless, I am aware that we live in a world where little gets done without some level of compromise. Yet wilderness and related natural landscape protections stand alone, different from other social and environmental issues in a couple of important ways. Wilderness represents the antitheses of civilization’s unrelenting quest to tame, dam, pave, graze, cultivate, control and mold the world into and unnatural quagmire for human convenience. And once wilderness is defaced, it is usually gone for good. In the contiguous United States, about 90% of the wilderness has already been compromised away. Can’t we save the remaining 10% of the landscape? To resist further compromise isn’t “radical”. It’s common sense. It should behoove the conservation movement to do everything within its power to resist further compromise of wildlands. And let’s also restore key wildlands that have been degraded. E.O. Wilson suggests that 50% of the Earth’s landscapes should be protected as nature reserves. Clearly, we have a long ways to go.

By contrast, the old fashioned way requires a long-term commitment to educating and organizing, so that the general public learns that wilderness is far more than a primitive recreation area, not just a pie to be chomped down and divvied up among user groups. It also requires the strength of character to avoid beginning a process by compromising with opponents, and by fighting for every possible acre thereafter as the process proceeds. This requires leadership that loves and values wilderness as the highest expression of human selflessness: as a biocentric entity with intrinsic value just because it exists as a wild place. That mentality is often lacking in today’s conservation movement.

I am aware of today’s considerable social and political barriers to enacting clean wilderness bills (those with no special provisions) that include most or all of the available wildland entity. They are formidable. I get that. I realize that todays’ public land debate is a complex beast in an increasingly complex world. For example, mountain bikes didn’t even exist prior to the 1980’s. But now, mountain bikers (mostly young, physically fit socially liberal outdoor enthusiasts) are a major anti-wilderness lobby. And because today’s snow-machines can tackle much tougher terrain compared with those of the past, snowmobiler opposition to wilderness designations has grown accordingly.

So, in today’s global social and environmental shitstorm of climate crisis, overpopulation and the biological meltdown (the ongoing human-caused extinction event) – not to mention wars, racism and the demise of democracies – it is not surprising that wilderness flies below the radar of many activists. And when you fail to recognize the importance of something, it is easy to compromise it away.

But still. Still thriving deep in my cranium’s long term memory synapsis I can recall a better way. I recall when folks like Bob Anderson and Randall Gloege and their Senate champion Lee Metcalf (D-MT) simply wouldn’t accept a divided Absaroka-Beartooth wilderness. Today, the greater Absaroka-Beartooth wildland is a 1,249,000-acre unbroken expanse of wild country (acreage from The Big Outside), dominated by the officially protected 944,000-acre Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness.

The battle to enact the 1964 Wilderness Act itself was before my time, but Howard Zahniser and crew didn’t get LBJ’s signature on the bill by being meek and making it palatable to every self interest group. Yes, there were unfortunate political compromises along the way – for example, to accommodate mining claims through 1984 and to grandfather in livestock grazing -- but our side fought to minimize these special provisions. I cannot help thinking that given today’s mindset, were the Wilderness Act on the 2021 political docket, the National Wilderness Preservation System would more resemble Disneyland than real wilderness.

Political victories don’t emerge from the woodwork; nor from wishful thinking. They require a full-time commitment to public education and grassroots organizing. As long-time activist Brock Evans put it, they require “endless pressure endlessly applied”. Congressional wilderness champions such as Lee Metcalf were possible only because Congress perceived that voters wanted big wilderness. I am not naive enough to believe that there is any kind of quick fix for the conservation movement in these complex and frightening times. I fully realize that it may be too late in the climate game to save much of anything. Yet the Thirty by Thirty and Half Earth movements provide a ray of hope. Birth rates in many parts of the world are declining (though not enough). And if we don’t try, we guarantee failure. Designating big holistic wilderness and keeping it wild needs to be a priority if we are to slow the biological meltdown and maintain some level of long term wildness and naturalness on this beleaguered planet.

To summarize, wilderness is primarily about habitat, wildlife, biodiversity and the intrinsic value of wild landscapes. Big wilderness defines our healthiest landscapes, be they forest, desert, prairie, tundra or combinations of diverse habitats. Wilderness is also about non-mechanized recreation, yes, and related spiritual values including solitude. But recreation and solitude are not its primary purpose, and our remaining wildlands are far more than an outdoor gymnasium.

Real wilderness is the primary control area in the vast experiment called human civilization. For how else can we measure the health of civilization except to compare it with unspoiled nature? All wilderness and semi-wilderness lands have conservation value. But protected wilderness ought to be as large as possible. It should be kept wild, without human manipulation and without livestock grazing. It should be managed under the Wilderness Act without special provisions that weaken protections.

Wilderness boundaries should also reflect the actual wildland entity on the ground, rather than the artificial borders of BLM or ranger districts, county lines, state lines, and old incomplete agency roadless area inventory borders.

Where feasible, wildland units should be interconnected or proximate, without barriers to wildlife movement. And wilderness areas should have holistic boundaries that minimize edge and maximize interior remoteness. Big, wild remote holistic wilderness is the cradle of all life on Earth and needs to be treated as such. Small fragmented edge-dominated oddly-shaped wildlands are better than nothing, sure, but they don’t fully maintain the core values of wilderness that are so important on this otherwise human-dominated planet.

In a sane world, overpopulation, the climate crisis, and the ongoing biological meltdown would top most any thinking person’s political agenda. Big holistic wilderness is intricately linked to all three. If the so-called “big greens” won’t lead the charge, unapologetic and with passion, based upon good science and biophilia, then they need to get out of the way of those who will.

------------------

Howie Wolke recently retired from 41 years of outfitting and guiding wilderness backpack treks from Alaska to Mexico. He is on the Wilderness Watch board of directors and has been a wilderness advocate in the northern Rockies since 1975. He lives with his wife Marilyn Olsen and their dog Rio in southern Montana near Yellowstone National Park.

All photos © Howie Wolke. From top to bottom: Washakie Wilderness, South Absaroka Complex, WY; Escalante Canyons Proposed Wilderness, UT; Buffalo Horn Drainage, Gallatin Range Proposed Wilderness, MT; Grizzly Bear, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Wilderness, AK.

by Roy (Monte) High

by Roy (Monte) High

Over the years I’ve heard numerous people disparage the designation of wilderness areas by speaking on behalf of people with disabilities. They say that wilderness areas are unfair to the disabled because there are no roads allowed to take them there. I’ve heard it said that the designation of wilderness areas is like a slap to the face of the disabled population. As a person with a disability, I wholeheartedly disagree.

In 1983, as a 20-year-old boy, I was driving along a small winding highway between Dolores and Cortez, Colorado when five horses ran out in front of me. The ensuing collision caused a spinal cord injury that left me paralyzed, a quadriplegic with limited movement below the neck. I have now lived most of my life navigating the Earth in a wheelchair.

Before the crash I was very physically active, and spent much of my time in the great outdoors—hiking, hunting, fishing, camping, being. Some of my best memories are of traversing the tree line—hiking along rushing streams, through mountain meadows, aspen and pine, to come face to face with rocky outcroppings. Walking through the wild wonder. Otherworldly surroundings. The silence—there is sound, but no noise. Just the soothing sound of nature. I’d sit still and listen, and move on with a renewed sense of belonging. I am reminded of the connectedness of all things, that everything is one in God. I am awakened to reality, aware of my place on the sacred path I follow as a human being. O the beauty! O the peace, the exaltation of my soul! Even now, as I write these words the beauty brings me to my knees in reverence, tears roll from my eyes. The tears come not because I can no longer visit these pristine places, but because these places exist—just knowing that such beauty exists within our world brings me joy.

I still love getting out into nature. There are many beautiful natural areas that I can access in my wheelchair, places I can sit where it seems as if I am out in the middle of the wilderness, where I can recharge my connection to nature, experience a sense of immediacy and enter wholly into the moment. I live in Grand Junction, Colorado. I love spending time on trails along the Colorado River and the local state parks. Wheelchair accessibility has come a long way in recent years. I am grateful. Yet, I am aware of the need for designated wilderness areas and I am grateful for the wild places where wildlife can thrive.

As a wheelchair user I have learned to adapt. There are many places that are not accessible to me, including many of my friend’s homes. I do not take this as a sign that I am not welcome. I do not expect my friends to spend thousands of dollars to remodel their houses just so that I can enter. There are many other places where we can meet, where my friends can welcome me into their hearts. Likewise, I do not expect anyone to build roads and trails over every square inch of wilderness so that I can visit in my wheelchair. Especially when I realize that my selfishness could lead to the demise of the very land I love. I love knowing that there are wild places where animals can room free without human disruption. Many species are going extinct. Some animals, such as elk, require large wildlife corridors for migration, and many species cannot survive around the noise and pollution of machines. These lands mean much more than how much money we can pump out of them—for much of God’s creation these wilderness lands are crucial for their survival.

------------------

Roy (Monte) High lives in Grand Junction, Colorado. He enjoys getting out into the natural areas nearby with his wife Elizabeth.

Wilderness Watch

P.O. Box 9175

Missoula, MT 59807

P: 406-542-2048

E: wild@wildernesswatch.org

Minneapolis, MN Office

2833 43rd Avenue South

Minneapolis, MN 55406

P: 612-201-9266

Moscow, ID Office

P.O. Box 9765

Moscow, ID 83843